Extracapsular Lateral Suture Stabilisation

ELSS stands for Extracapsular Lateral Suture Stabilisation, also known as a ‘lateral suture’, ‘extracapsular repair’, ‘fabellotibial suture’ or a ‘tibiofabellar suture’.

What is ELSS surgery?

How does ELSS surgery work?

The aim of ELSS surgery is to place a suture that prevents the two bones from moving too far apart, so that the tibia does not shift forward during weight-bearing. After a period of healing, the soft tissues around the joint form scar tissue around the knee, which provides support in the same way as the suture. Over time, the suture itself will weaken but by this point the scar tissue should have taken over its role.

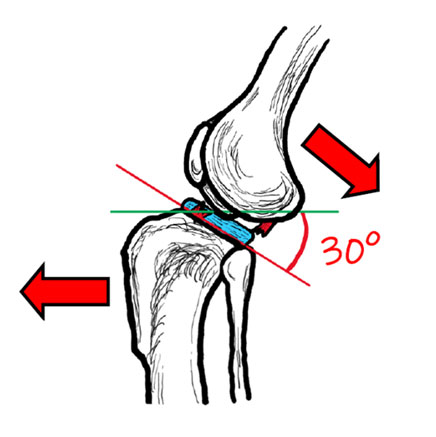

Image copyright of Rebecca Jones

Image of a canine knee joint with a torn cranial cruciate ligament.

The backwards slope of the shin bone causes the thigh bone to slip backwards in relation to the shin bone (and vice versa) if the cranial cruciate ligament is unable to resist this movement. The menisci are pictured here in blue – these are cartilage structures which act as shock absorbers within the joint.

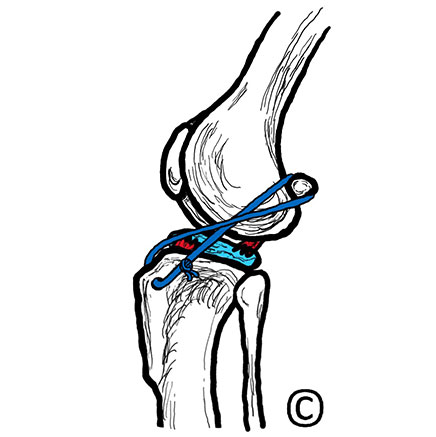

Image copyright of Rebecca Jones

Image of a canine knee joint after ELSS surgery.

A suture has been placed in a figure of eight pattern around the lateral fabella (a small bone behind the thigh bone) and through a bone tunnel made in the shin bone.

What does ELSS surgery involve?

All ELSS procedures are performed under a general anaesthetic. Your pet will likely need to have a full clip of the affected leg stretching from the ankle to the hip.

Generally, surgery will start with opening the capsule surrounding the knee joint and assessing for damage to the shock-absorbing cartilage pads that sit between the bones (menisci). If damage is seen, then the damaged portion is removed before the ELSS is performed. This may be done as an open approach or keyhole – with a specialised camera.

Following this, a small amount of dissection is performed to expose the fabella (a small bone behind the knee) and the top of the shinbone and one or two small tunnels are drilled through the latter. A thick nylon suture is then fed around or just above the fabella and through the bone tunnel(s), before coming back around onto itself in a ‘figure of eight’ pattern and being secured in place (usually by a metallic ‘crimp’, but sometimes by a knot). Different materials may also be used and some ‘all-in-one’ systems, e.g., Tightrope, are available.

The joint is then closed in an ‘imbricating’ pattern – this helps to encourage formation of the scar tissue which will ultimately stabilise the joint.

What does post-operative care involve?

Medication

Your dog will require a course of pain relief and sometimes antibiotics following surgery; these are typically given orally in tablet or liquid form.

Exercise

Exercise is beneficial during the recovery, although this must be strictly controlled and will be significantly reduced during the first six to eight weeks following surgery. A period of very strict exercise restriction is likely immediately after surgery and will require your dog to be crate-rested or confined to a small room without access to furniture. Your surgeon will provide you with more detailed instructions on how to manage your dog’s exercise following surgery.

Follow up visits

Depending on how your pet’s surgical wound has been repaired, a follow-up visit to your vet is often needed around two weeks after surgery. Most dogs will need to wear a buster collar until this time to prevent interference with the wound which may lead to infection.

Weight control

Unfortunately, regardless of treatment (or lack of treatment), all dogs are likely to be predisposed to the development of osteoarthritis in the affected joint following cranial cruciate ligament disease. Because of this, it is recommended that they maintain a slim body condition. Your vet will be able to give you more information regarding weight control plans if this is required.

Hydrotherapy/physiotherapy

Hydrotherapy and/or physiotherapy can be useful in the post-operative period and can be considered once the skin wound has healed. Your vet can advise you if this is appropriate for your pet.

What is the prognosis following ELSS?

All dogs with cranial cruciate ligament rupture are expected to eventually develop at least some signs of osteoarthritis in the affected joint, but this is likely to be reduced or delayed in dogs who have had a surgical procedure.

Around 50% of dogs will develop cranial cruciate ligament disease in the other hind limb; in some cases this requires immediate surgery, and in others, it may be many years.

What are the risks of an ELSS?

Unfortunately, complications can occur with any surgical procedure. The complication rate for ELSS surgery is low (approximately 7% of dogs required a second surgery in one study), but potential complications include:

Premature suture failure

If the suture breaks before the needed scar formation has occurred, then your dogs may suddenly become lame again.

Infection

Any surgery carries a small risk of infection. Orthopaedic surgery carries a slightly higher risk because bacteria can stick to the metal implants which makes is difficult for the immune system to reach them. To reduce this risk, all dogs receive antibiotics during surgery. If your dog licks their wound after surgery, they can introduce infection, which is why most dogs will need to wear a buster collar until the surgical wound has healed.

Subsequent meniscal injury

In up to 7% of cases, the menisci appear normal at the time of surgery but are later damaged due to continued, mild degrees of joint instability. Lameness may persist longer than expected post-surgery, or dogs may seemingly recover before suddenly becoming lame on the leg once more. If this occurs, repeat surgery will be required to inspect the meniscus for damage and cut away any torn portions.

Which dogs will benefit from an ELSS?

In general, ELSS procedures are more commonly advised in smaller or less active dogs. It has been shown that younger and larger dogs are more likely to experience complications following ELSS.

Contributors

Authors: Dr Simon Ratcliffe BVSc CertAVP(GSAS) MRCVS and Dr Catrina Pennington BVM&S MRCVS

Simon is a general practitioner, owning and running a small animal practice in Berkshire. He has always enjoyed surgery, completing his certificate in general small animal surgery and becoming an advanced practitioner in 2014. Ever since mixed practice as a new graduate in North Wales in 2005 Simon have been fascinated by cruciate disease and enjoys continuing to learn and improve treatment of this complex disease.

Catrina graduated from the University of Edinburgh in 2014. After two and a half years in small animal, first opinion practice she completed a rotating internship followed by a period as a surgical registrar at Chestergates Veterinary Specialist. She returned to Edinburgh University in 2018, completing an internship in Soft Tissue and Oncological surgery before starting her current position as a Clinical Fellow in Small Animal Surgery at the Royal Veterinary College.

Editor: RCVS Knowledge Communications Team

Reviewer: Mark Morton BVSc DSAS(Orth) MRCVS

References

- Casale, S. and McCarthy, R. (2009) Complications associated with lateral fabellotibial suture surgery for cranial cruciate ligament injury in dogs; 363 cases (1997-2005). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 234 (2), pp. 229-235. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.234.2.229

- Deangelis, M. and Lau. R.E. (1970) A lateral retinacular imbrication technique for surgical correction of anterior cruciate ligament rupture in the dog. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 157 (1), pp. 79-84.

- Gordon-Evans, W. et al. (2013). Comparison of lateral fabellar suture and tibial plateau leveling osteotomy techniques for treatment of dogs with cranial cruciate ligament disease. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 243 (5), pp. 675-680. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.243.5.675